Outline

1. Introduction

2. Walkers as Symbols

3. Rick Grimes’ Change

4. Rise of New Communities

5. Survival and Morality Challenges

6. Changes in Characters

7. Villains and Leadership Styles

8. Philosophical Ideas

9. Negan’s Power and Control

10. Conclusion

There’s a moment from The Walking Dead that stays with me: Rick Grimes standing in the ruins of a world that once made sense, his face etched with the weight of leadership, his eyes reflecting the uncertainty of everything that remains. This moment isn’t just about surviving the undead, it’s also a confrontation with the depths of human nature when the comforts of civilization are stripped away. The Walking Dead isn’t just a dystopian nightmare. It’s ann exploration of humanity’s fragile psyche and the moral decay that comes when societal norms collapse. It feels like a call into the Nietzschen abyss and confront what stares back.

The walkers themselves become almost peripheral, less antagonists and more like haunting symbols of decay. They’re external manifestations of the characters’ internal conflicts, the fears, regrets, and primal instincts that rise to the surface when the rules no longer apply. Much like the ocean in Lem’s Solaris, which materializes the deepest recesses of the protagonists’ minds, the apocalypse here serves as a canvas for exploring the raw, uncharted territories of the human condition. The true conflict isn’t the external threat of the walkers. It’s what happens inside the survivors as they’re forced to face their own moral ambiguities.

Rick’s transformation from law-abiding sheriff to someone who makes unimaginable choices is a Kafkaesque journey in itself, reminiscent of individuals lost within incomprehensible systems. His path is a labyrinth of ethical quandaries, each decision eroding his sense of right and wrong. You can feel the tension as his old world crumbles, and with it, his moral foundation. It’s a raw portrayal of what happens when the weight of responsibility threatens to crush the very humanity he’s fighting to preserve. His journey, like Didion’s reflections on grief, becomes one of survival in a world that no longer follows the rules he once knew.

As the series progresses, the communities that emerge: Woodbury, Terminus, Alexandria. They become microcosms of political ideologies in a post-collapse world. These settlements reflect the desperate attempts to rebuild society, but also the compromises and ethical trade-offs that come with power. The Governor’s authoritarian grip on Woodbury presents a veneer of normalcy, while underneath lies a chilling control that reveals the dangers of unchecked power. Terminus, on the other hand, pushes utilitarianism to its extreme, where survival justifies even the most horrifying actions. And then there’s Alexandria, a fragile attempt at democracy, offering hope, but always teetering on the edge of collapse.

What draws me to The Walking Dead is how it doesn’t give us clean answers. It’s not about finding the right path. It’s about grappling with the complexity of survival, morality, and leadership in a world that no longer has clear rules. This series doesn’t just ask what it takes to survive. It asks what we’re willing to become in the process. It reminds me of Peter Watts’ Blindsight, probing the limits of human understanding and forcing us to confront the parts of ourselves we’d rather not face.

In this redefined world, characters undergo profound transformations. Carol, once vulnerable and underestimated, becomes a symbol of resilience. Her journey is one of survival and reinvention, raising questions about identity and the lengths we’ll go to protect the ones we love. It’s a theme that resonates deeply, how loss, like grief in Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, reshapes our understanding of who we are and what we can endure.

Michonne’s arc is equally powerful. Initially a solitary cool samurai figure, hardened by the brutality of the world, she evolves into someone who allows herself to reconnect, to trust, and to find humanity again amidst the chaos. Her relationships, especially with Rick and their group, become a testament to the importance of community, even when everything around them is crumbling.

And then there are the antagonists like the Governor and Negan, who embody different visions of leadership in the apocalypse. The Governor’s descent into madness reflects the corrupting influence of power, while Negan, with his brutal code, represents a twisted utilitarianism, sacrificing the few for what he sees as the greater good. Both characters force us to question the nature of power, morality, and control when there are no longer systems of accountability in place.

Drawing from Nietzsche, the series delves into the concept of the Übermensch and the necessity of reevaluating values when the traditional moral frameworks disintegrate. Characters like Rick, Carol, and Michonne are left to construct their own ethical codes, leading to moments of ethical relativism where survival often outweighs conventional morality. The abyss Nietzsche speaks of, the one that stares back, becomes a metaphor for the psychological toll of living in constant proximity to death and moral compromise.

“I Am Negan”

Foucault’s ideas on power and discipline resonate throughout The Walking Dead. The show illustrates how, when conventional systems of power collapse, new structures emerge from the ruins. These new power dynamics are often based on fear, surveillance, and the control of bodies and behavior. Foucault’s vision of power as pervasive, not limited to formal institutions, is made real in the struggle for dominance in the post-apocalyptic world. The Governor and Negan, with their oppressive regimes, are examples of how power morphs into something darker when it is untethered from accountability. Their rule isn’t just about survival; it’s about control over the physical and psychological lives of their people, referencing Foucault’s notion of biopower.

Negan’s rule in the later seasons, particularly the “I am Negan” philosophy, presents a different take on power compared to the Governor’s more isolated, authoritarian control. Where the Governor ruled through fear and spectacle in Woodbury, Negan creates a decentralized system of biopower, where surveillance is not just top-down but embedded within the community itself. Every individual in the Saviors becomes part of the surveillance network, monitoring each other and reinforcing Negan’s control. By having his followers declare “I am Negan,” he extends his power through them, dissolving individual identities into a collective where everyone is an enforcer of the system.

This structure of surveillance and control is more insidious than the Governor’s overt authoritarianism. Instead of ruling through sheer terror, Negan’s system functions by creating a network of loyalty, fear, and complicity. His lieutenants, the workers in his compound, and even the communities under his thumb all operate within this network, constantly being watched and watching others. It’s a more subtle form of biopower, where Negan’s influence permeates every level of the organization, making rebellion almost impossible. The power isn’t just concentrated in Negan himself but dispersed across the people who identify with him and enforce his rules.

Foucault’s ideas on surveillance as a mechanism of control are clearly at play here. The omnipresence of Negan’s network mirrors Foucault’s notion of the panopticon, where the possibility of being watched keeps people in line, even if they aren’t being actively observed. In this way, Negan’s “I am everywhere” mentality is an evolution of the Governor’s rule. While the Governor relied on fear and intimidation, Negan creates a self-sustaining system where the people he controls actively reinforce his power.

In summary

The Walking Dead is a powerful commentary on the fragility of civilization and the psychological burden of survival. It asks uncomfortable questions about who we become when the world we know is gone and forces us to confront the darker parts of ourselves. Like Didion’s reflections on grief, it holds a mirror up to our vulnerabilities, our capacity for resilience, and our need for connection, even when everything around us is falling apart.

In a playfield of political theories, The Walking Dead isn’t just about the apocalypse. It’s about the human condition, the capacity for both cruelty and compassion, the struggle to maintain our sense of self when the world is unrecognizable, and the deep, existential question of what it means to be human in the face of unrelenting adversity.

Book Recommendations

1. “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” by Friedrich Nietzsche

Examines the idea of the Übermensch and questions traditional morals, similar to how characters in The Walking Dead shift their ethics in a collapsed society.

2. “Discipline and Punish” by Michel Foucault

Studies power, surveillance, and control in society, reflecting the new power structures in the post-apocalyptic world of the series.

3. “The Trial” by Franz Kafka

A story about someone lost in a confusing system, paralleling Rick’s unsettling journey through a world of unclear rules.

4. “The Year of Magical Thinking” by Joan Didion

A deep look at grief and loss, relating to how characters change and cope with ongoing hardship.

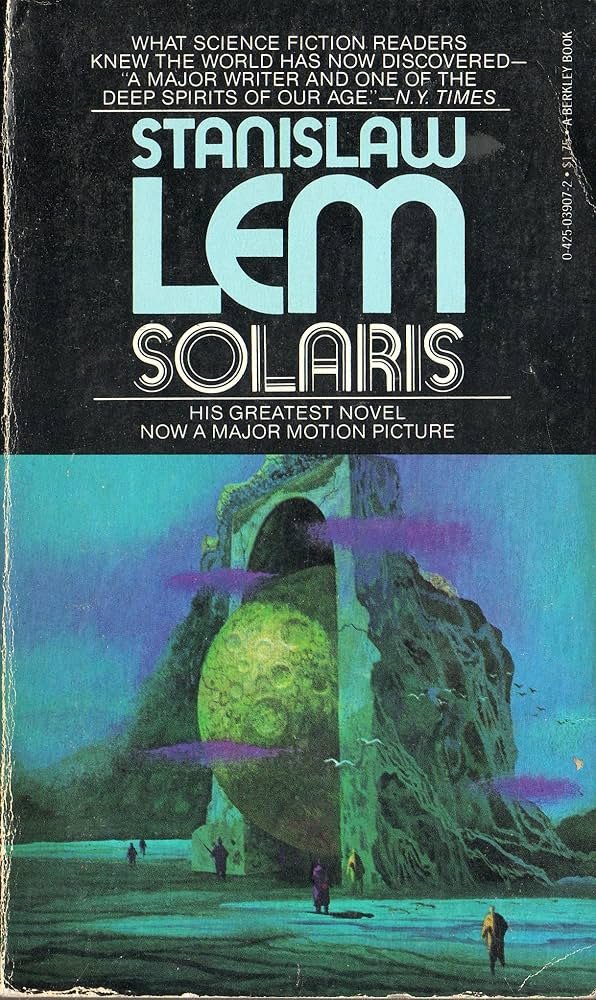

5. “Solaris” by Stanisław Lem

Science fiction that explores human consciousness and inner conflict, like how walkers represent the characters’ deepest fears.

6. “Blindsight” by Peter Watts

A novel that challenges our understanding and self-awareness, reflecting the show’s investigation of humanity under stress.

7. “Lord of the Flies” by William Golding

Looks at the collapse of social order and the fall into savagery, mirroring the moral dilemmas faced by survivors.

8. “1984” by George Orwell

Discusses totalitarianism and control, similar to the oppressive leaders like the Governor and Negan.

9. “Station Eleven” by Emily St. John Mandel

Follows survivors after a pandemic, highlighting art, memory, and rebuilding society.